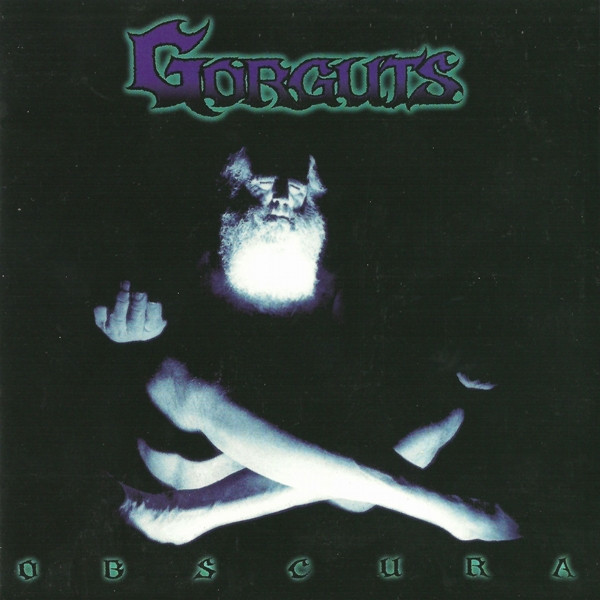

I’m listening to Gorguts’s Obscura.

I often don’t listen to it because I can’t listen to it while doing other things, but I am on a plane now, not doing other things.

A lot has been said about this album because it is a landmark progressive metal album. And yet now I feel like saying even more about it and about how we perceive music.

At the time it was released in 1998, nothing was like it, including Gorguts’s previous albums, which were very straightforward death metal.

It’s considered very technical, and it certainly is challenging music to play. But it does not really sound technical the way, say, Origin or Gorod sound technical. When those bands play, you more or less know what is being played, even if you are blown away by how it is behing played. Whereas with Gorguts, there’s some uncertainty about what is even happening.

First and foremost, the album sounds alien. It’s dissonant, but not sequentially, like when Black Sabbath hits the tritone after establishing the root, but harmonically, with the root and tritone (and other dissonant combos) being played at the same time.

Plenty of bands have tried this. It always sounds to me at worst like a gimmick and at best a curiosity. I usually tune it out. I’m not completely sure how Gorguts are able to avoid making such high incidences of dissonance numbing!

There’s also very little chugging. When there is, it’s in one guitar part, while the other is playing something that rings. (Chugging is palm muting while picking with a sharp attack with distortion on. From about 1983 on, it has been a staple of metal.)

Single favorite sounds aren’t very important because no sound alone can make a piece of music work. Still, if I had to pick a single best sound in music, chugging is it. Sometimes, if I’m feeling workday emotional death, I turn on my tiny amp and chug for a few seconds to pump myself up.

Instead of chugging, Gorguts plays a lot of open-sounding riffs. I imagine there’s open strings in the chords in those riffs, but there might not be. Either way, the strings ring and clash with each other.

When Obscura came out, I remember thinking, why do I think this is metal? I checked the forums, and yes, “everyone else” also thought it was metal.

I went to see them (though admittedly, I mostly went to see Cryptopsy, their more traditional — but still relatively inventive — fellow Quebeckers). At the show, people were reacting to their performance the way they’d react to Morbid Angel. It was metal.

I’m not at all oppsoed to Obscura being considered considered metal. It’s that I’m still a little amazed that it went over as metal. Harmonically and melodically, the riffs are very far away from what Chuck Schuldiner would have written. Rhythmically, though, there are familiar cadences, especially in Subtle Body and the title track, in which dissonant squeals are ordered by a very headbanging triplet sequence. On the other hand, there’s also what sound like free time slowdowns.

Gorguts made a pact to not have any Slayer beats on the album, but there are blast beats and double bass here and there. And familiar death metal vocals provide additional anchoring.

I think a lot of how it landed as metal has to do with extrasonic context. Gorguts had two traditional death metal albums out to stand on. They are named Gorguts, not Negativa or Lotus Mind or something that could be an avant garde jazz project.

At the show I went to, they brought Jim from Oppressor on stage to sing a song with them. (At the time, I assumed he was Oppressor’s vocalist, but I now see that he was their guitarist.) Luc Lemay gave Jim a hug. Oppressor had just broken up so the other members could work on an explicitly commercially-oriented rock band called Soil. That’s one of the saddest possible ways for a death metal band to end. Anyway, Gorguts were clearly well-rooted in the metal community.

For whatever reason, I used to believe long ago that a piece of music’s “merit” comes purely from its sound. This isn’t true, and in fact, cannot be true.

No music exists independent of extrasonic context, even if the context is that you found a song by clicking on a tag on Bandcamp. Even if you know nothing else about the song, your perception is informed by knowing you got to it from that tag.

If you like a crust punk band said to be made by anarchists, and they turn out to be the sons of Pentagon bigwigs, should you then not like it? Sure! Because that story was part of the music. (Or maybe it wasn’t, and you should keep listening to the military-industicrust!) The same goes for liking Beyoncé’s music because she’s a powerful woman in non-sound contexts. Her persona and stage show are part of the music, just like her voice is.

I’ll go further and say that no two listens of any piece of music will ever be the same for you, regardless of the story of the artist. Even if your cochlear cilia move exactly the same way on every listen, your own life and the billions of pieces of state in your brain will never be the same at any two moments in time. Your brain state is part of the experience.

So, Obscura is a metal album despite falling far outside of metal’s sonic “centroid”. But did it expand metal?

There is a group of dissonant death metal bands like Ulcerate and Pyrrhon. (I should mention that Gorguts’ Quebecois predecessors Voivod also did a lot with dissonance well before Obscura. I just wasn’t into it for whatever reason.) It’s a small group, though, considering it’s been 25 years since Obscura’s release. I think this is to be expected. The more established an art form gets, the harder it is to change.

Metal is ossifying. If I was going to be more dramatic, I’d say “dying”. But I think ossifying is more accurate. It’s not that different from the ossification of blues (which is over a century old) and jazz.

You can argue that these art forms are not ossifying because people make new blues and new jazz all the time, and still more people enjoy the new blues and new jazz. But I would say that new stuff is not vital.

I’m not sure I can explain “vital” well, but there is a difference between a piece written by Bach and a piece written in the 20th or 21st century by a person that thinks Bach kicks ass. Likewise with the Ramones and Ramonescore and Miles Davis and Wynton Marsalis.

New work in these genres is more “interesting” or “comforting” rather than vital. That isn’t bad, but it is a sign that a form is so well-explored that mostly what’s left to do is to revisit spaces that we remember were really good.

Old genres (metal is 53 years old at least) have this catch-22 in which new works often end up either revisiting old territory (which again, is sometimes nice!) or being different enough from existing works in the space that they’re no longer considered part of the genre.

I don’t think this is sad. Nor do I think it is avoidable. Nothing lives forever, and every vital space eventually fills up.

When Obscura was released, metal was about 28 years old (which is still pretty old for a popular music genre), and I’ll say again, it was sonically way outside the averaged boundaries of the space. Getting people to listen to something unfamiliar is the composer’s hardest task. And they totally did that.

The compositions themselves are compelling, but being considered metal was part of making that happen.

And they did it not just for themselves, but for the listeners. When I sit down and spend an hour with Obscura, I’m taken to a genuinely different mental space. It is alien but not alienating. Once I am fully immersed in that space, it’s super refreshing. (I hate to make it sound like an iced coffee, but I can’t think of anything else.)

Thank you, Gorguts!

Update, 8/25/2023

After posting this, I watched a bookmarked video and realized Gorguts had played a lot of this material in 1995 at the Thirsty Whale (a predecessor to Smiler Coogan’s in Chicago), four years before I saw them and three years before the album even came out. I had read that they had recorded it well before they could find a label to put it out, but I didn’t quite think it was just one year after their previous album.

They definitely sold it. The first Obscura song starts about nine minutes into the set, and people are still moshing. A few people even get on stage. Luc Lemay says nothing about how it is completely different from the albums the audience actually knows. They just say “from the new album”.

There’s definitely a lot more headbanging than when they performed in 2013 at Saint Vitus, though. At that point, however, they didn’t need to sell this sound at all.